SUPERCHARGE YOUR Online VISIBILITY! CONTACT US AND LET’S ACHIEVE EXCELLENCE TOGETHER!

There was a moment—quiet, almost unremarkable—when searching stopped feeling necessary. A question surfaced, as it always does, but instead of opening Google, scanning a list of links, and piecing together an answer, the reflex changed. We opened ChatGPT. Or Perplexity. Or any number of AI-powered answer engines. We asked. We received. And we moved on.

No tabs. No skimming. No weighing one source against another. No half-formed doubt that nudged us to scroll further or refine the query. The answer arrived complete, confident, and neatly packaged. The friction that once defined information-seeking simply vanished.

This stands in sharp contrast to the old Google ritual that shaped how an entire generation learned to think online. A query led to ten blue links. Those links demanded judgment—Which one looks credible? Which one feels biased? Which one actually answers what I meant to ask? Understanding emerged not from a single response, but from comparison, synthesis, and small acts of skepticism. Searching was not passive; it was participatory.

This is where the uncomfortable thesis begins. Google trained us to search. Answer engines are training us to accept. The shift is subtle but profound. It’s often framed as a story of efficiency—faster answers, fewer clicks, less wasted time. But efficiency isn’t the real issue. What’s happening is cognitive outsourcing: the gradual transfer of thinking tasks we once performed ourselves to systems designed to think on our behalf.

That’s why this conversation matters far more than SEO, content traffic, or publisher economics. The true disruption isn’t technological or commercial—it’s epistemic. We’re not just changing how we find information; we’re changing how we engage with knowledge itself. The habits we’re forming now will shape how we question, doubt, and understand the world.

This article argues that search engines cultivated active cognition by forcing users to evaluate and synthesize. Answer engines, by design, encourage passive consumption. The trade-off is clear: unprecedented speed in exchange for reduced mental engagement. And we’ve barely begun to notice the cost.

How Google Taught an Entire Generation to Think in Queries

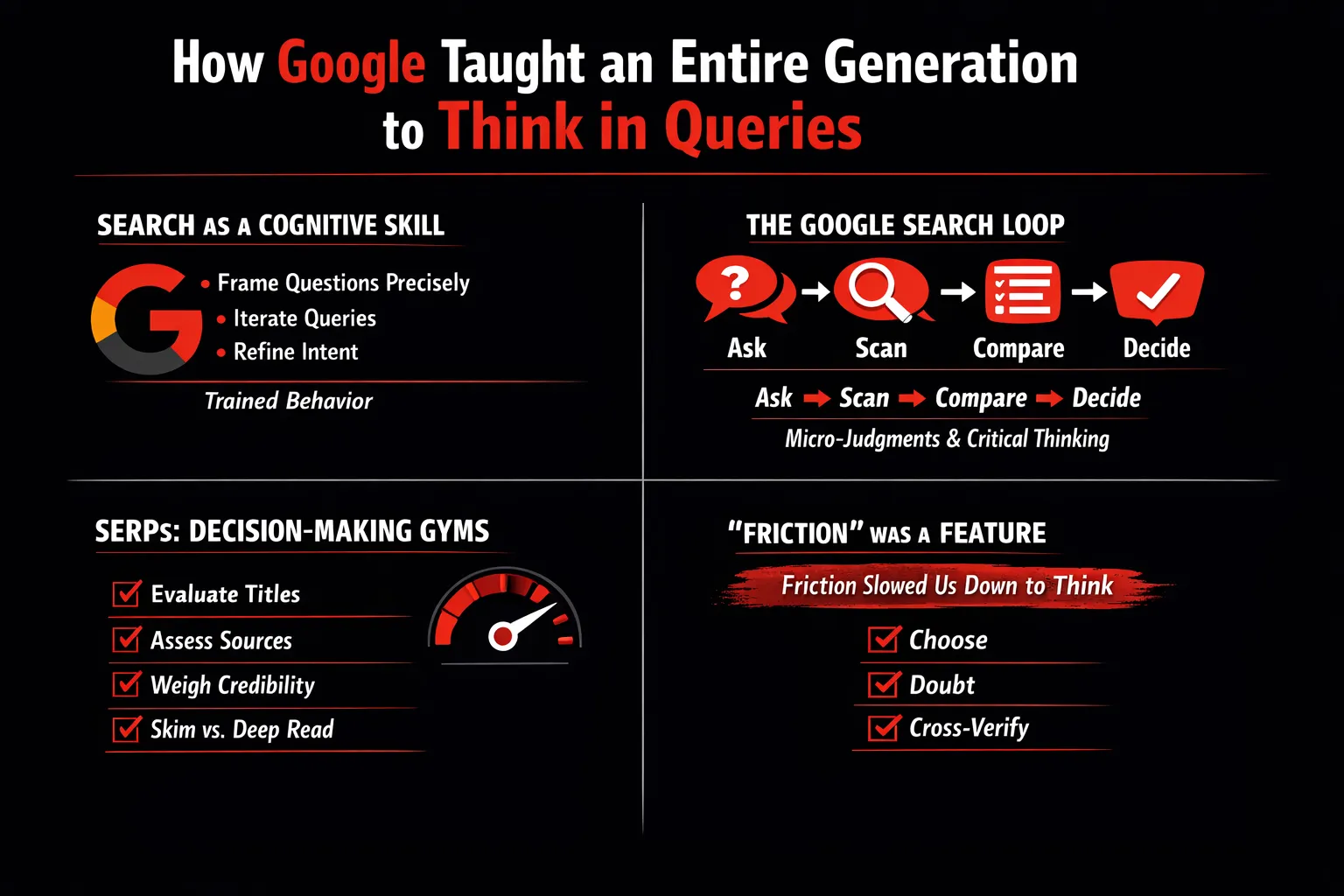

Google did far more than organize the web. Over two decades, it quietly trained human behavior. What began as a simple search box evolved into a global cognitive interface—one that taught millions of people how to ask, how to refine, and how to think through information problems. Search was not instinctive; it was learned.

Early users quickly discovered that vague questions produced weak results. To get useful answers, you had to be precise. You learned to strip emotion from a question, reduce it to keywords, and anticipate how the machine would interpret intent. Over time, this became second nature. People learned to frame questions strategically, to reword them when results missed the mark, and to iterate until the output matched the underlying need. Searching was an active dialogue between human and system, even if the system never spoke back.

This process created a familiar mental loop: ask, scan, compare, decide. You posed a question, scanned multiple results, compared perspectives, and then made a judgment. Each step demanded small but meaningful cognitive decisions. Which link looks credible? Which source aligns with my intent? Is this result too shallow, too old, or too biased? Search required engagement, even when the task was simple. In that sense, Google search functioned as a form of lightweight critical thinking, exercised dozens of times a day.

Search engine results pages (SERPs) became informal decision-making gyms. A user learned to read between the lines of headlines, recognize clickbait, and spot authority signals. Domain names mattered. Publication reputations mattered. Even the phrasing of a title influenced trust. Users subconsciously weighed credibility indicators—official sources, familiar brands, academic references—long before clicking anything. They also learned to skim efficiently, extracting value from snippets while deciding whether deeper reading was worth the effort.

Importantly, Google forced a choice between skimming and deep reading. Some queries demanded quick answers; others required long-form engagement. That decision itself was cognitive work. Search didn’t just deliver information—it trained judgment.

What many now forget is that the friction in search was not a flaw; it was a feature. The need to scroll, compare, and cross-check slowed thinking just enough to activate reasoning. Google rarely told you what to think. It presented options and forced you to choose. It encouraged doubt by default, because no single result ever felt final. To reach confidence, users had to triangulate across sources.

In doing so, Google taught an entire generation a subtle but powerful habit: thinking happens between answers, not inside them.

The Rise of Answer Engines: From Discovery to Delivery

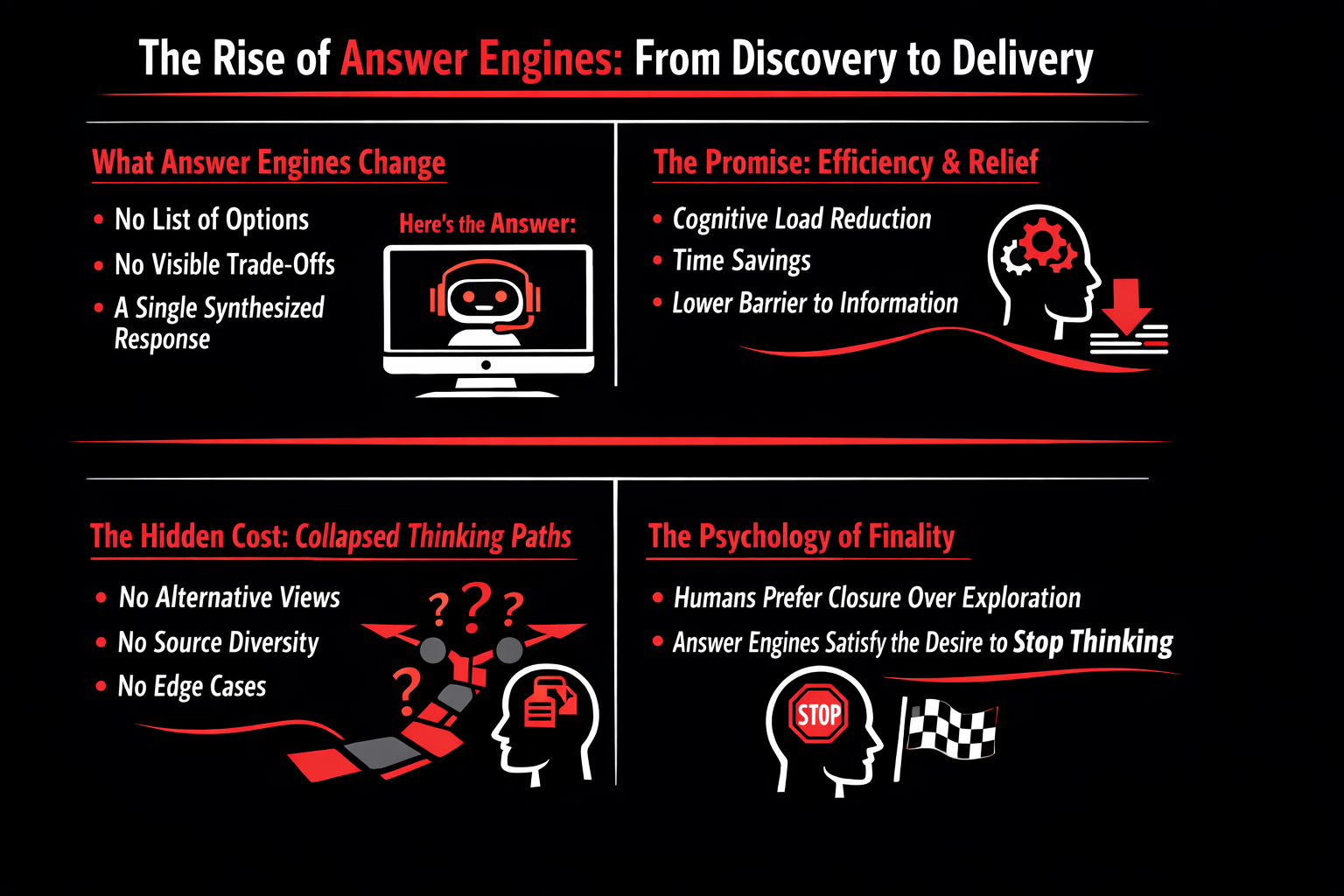

The most radical shift introduced by answer engines is not technological—it is experiential. Search engines were built around discovery. Answer engines are built around delivery. That single difference quietly rewires how users interact with information.

Where Google presents a list of possibilities, answer engines present a conclusion. There are no ten blue links to compare, no competing headlines hinting at disagreement, no subtle cues that signal uncertainty or bias. Instead of options, users receive a single, synthesized response—clean, confident, and authoritative in tone. Trade-offs disappear from view. The friction of deciding which source to trust is removed entirely because the system has already decided on the user’s behalf. What once felt like an open-ended exploration now feels like a transaction: ask, receive, move on.

This design choice comes with an obvious and powerful promise—efficiency. Answer engines dramatically reduce cognitive load. They spare users from scanning pages, evaluating credibility, and stitching together fragmented ideas. In a world defined by information overload, this feels like relief. Tasks that once took minutes now take seconds. For many users, especially non-experts, answer engines lower the barrier to knowledge that previously required time, literacy, and confidence to cross. The appeal is undeniable: less effort, faster results, fewer decisions.

But this efficiency masks a subtler cost—the collapse of thinking paths. Search exposed users to multiple perspectives by default. Even a simple query surfaced disagreement, nuance, and variation. Answer engines compress that complexity into a single narrative. In doing so, they eliminate accidental learning. Users no longer encounter alternative viewpoints unless they explicitly ask for them. Source diversity becomes invisible. Edge cases—those uncomfortable, inconvenient details that complicate understanding—are often smoothed out in favor of coherence. The answer may be correct, but it is rarely complete in a way that invites deeper thought.

What makes this shift so powerful is its alignment with human psychology. Humans are not wired to enjoy uncertainty. We seek closure. We want the feeling of “done.” Answer engines deliver that feeling exceptionally well. A clear answer provides psychological relief—it signals that thinking can stop. There is no lingering doubt, no need to explore further unless something feels obviously wrong. In contrast, search keeps curiosity alive by leaving questions partially unresolved.

Answer engines succeed not just because they are faster, but because they satisfy a deeper desire: the desire to conclude, to reduce ambiguity, and to move on. And in satisfying that desire, they quietly train us to value finality over exploration—answers over understanding.

From Active Searchers to Passive Receivers

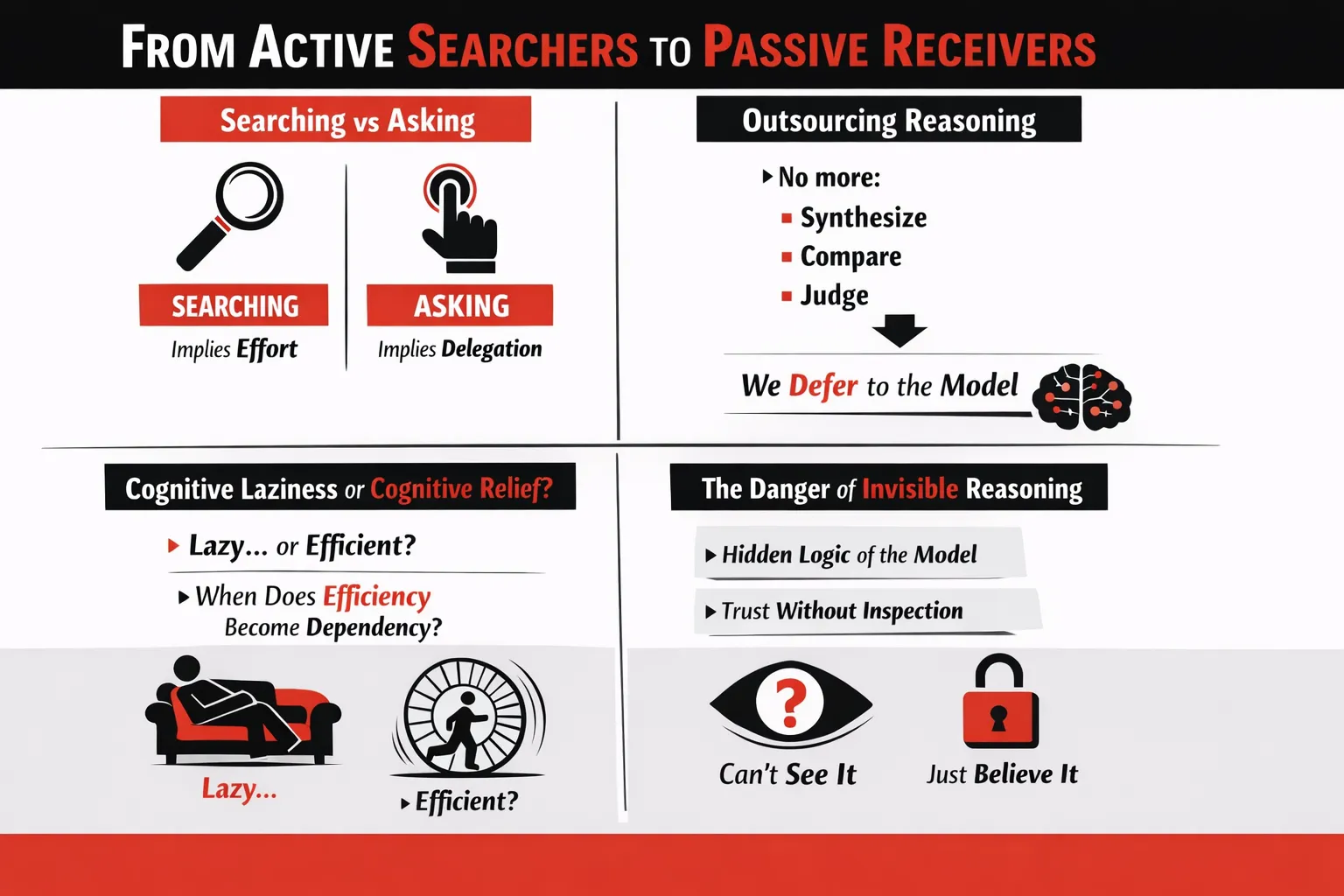

The shift from search engines to answer engines marks more than a technological upgrade—it represents a behavioral change in how we engage with knowledge. At the heart of this shift lies a subtle but crucial distinction: searching versus asking. Searching implies effort. It requires the user to articulate intent, evaluate multiple sources, and assemble meaning from fragments. Asking, by contrast, implies delegation. The cognitive burden is transferred elsewhere, and the user waits for a resolved output.

When we searched on Google, we were participants in the thinking process. Even poorly phrased queries demanded refinement. Even simple questions exposed us to multiple interpretations. The act of searching trained us to tolerate ambiguity and navigate it. Asking an answer engine, however, collapses this process into a single exchange. The system does the exploration; the user consumes the result.

This delegation leads directly to the outsourcing of reasoning. In traditional search, users had to synthesize information from different pages, compare conflicting viewpoints, and judge credibility based on context, authorship, and consistency. These steps were not optional—they were embedded in the experience. Answer engines remove that necessity. The synthesis is pre-packaged. The comparison is invisible. The judgment has already been made, not by the user, but by a probabilistic model trained on aggregated data.

Over time, this changes cognitive habits. We stop practicing the mental muscles required for evaluation because they are no longer demanded. The model becomes the default arbiter of relevance and correctness. While the output may often be accurate, the process by which we arrive at “knowing” has fundamentally changed. Understanding is replaced with acceptance.

This raises a difficult question: are we becoming cognitively lazy, or simply more efficient? There is no denying the relief answer engines provide. They reduce friction, save time, and eliminate the need to wade through irrelevant content. In many contexts—technical troubleshooting, quick factual lookups, first drafts—this efficiency is undeniably beneficial. But efficiency becomes problematic when it turns into dependency.

The line is crossed when users no longer feel capable of reasoning without assistance, or when they stop questioning answers because the system has earned their trust through consistency. At that point, the tool is no longer augmenting cognition; it is replacing it. What began as relief risks becoming reliance.

The most subtle danger lies in invisible reasoning. Answer engines do reason—often impressively—but that reasoning is hidden behind fluent language and confident tone. Users see conclusions without seeing the path taken to reach them. Without exposure to intermediate steps, assumptions, or uncertainties, trust becomes automatic. Inspection feels unnecessary. Skepticism fades.

This is a sharp departure from search, where the reasoning path was externalized across multiple links, perspectives, and contradictions. Users could see disagreement. They could trace arguments back to sources. With answer engines, reasoning is internal, opaque, and largely unverifiable in everyday use.

As a result, trust without inspection becomes the default behavior. And when that happens, the user’s role quietly shifts—from active participant in knowledge creation to passive receiver of information. The cost of that shift is not immediately visible, but over time, it reshapes how we think, decide, and ultimately, understand the world.

What We Lose When We Stop Searching

When search disappears, something subtle but important goes with it. The loss isn’t just about fewer clicks or less web traffic—it’s about how our minds engage with information. Searching forced us into a posture of active doubt. Answer engines, by contrast, often place us in a posture of passive acceptance. Over time, this shift changes how we question, how we understand, and how broadly we think.

1. The erosion of skepticism

Search engines implicitly encouraged skepticism. When Google returned ten blue links, it quietly asked the user to judge: Which of these is trustworthy? Which one should I open? Even before reading, we compared domains, titles, dates, and tones. Disagreement was built into the interface—multiple answers coexisted, often contradicting one another.

Answer engines reduce the need for this skepticism. A single, confident response removes the friction that once triggered questioning. There are fewer reasons to doubt because there are fewer visible alternatives. The answer arrives pre-processed, already filtered, summarized, and resolved. As a result, users are less likely to ask, Is this right? and more likely to ask, What’s next?

Over time, this trains us to trust outcomes without inspecting the process. Skepticism, once a default behavior, becomes optional—and eventually rare. When disagreement is hidden, the habit of questioning weakens.

2. Loss of contextual understanding

Searching was never just about reaching an answer; it was about traveling through context. Clicking multiple links exposed us to definitions, edge cases, historical background, and competing explanations. Even when we were looking for something specific, we absorbed surrounding knowledge almost accidentally.

Answer engines compress this journey into a conclusion. We get the “what” without the “why,” the result without the reasoning path. Background information becomes invisible unless explicitly requested, and most users don’t request it. The journey—the intellectual movement from uncertainty to clarity—is replaced by instant resolution.

This matters because understanding is built through progression, not just endpoints. When conclusions arrive without journeys, knowledge becomes brittle. It’s easier to forget, harder to adapt, and more difficult to apply in unfamiliar situations.

3. Reduced creative connections

Search had a unique side effect: serendipity. While looking for one thing, we often discovered another. A slightly off-topic article, an unexpected forum discussion, or a tangential idea could spark new insights. These “useful distractions” weren’t inefficiencies—they were sources of creativity.

Answer engines prioritize finality. They aim to minimize deviation, not encourage exploration. By design, they remove the noise—and with it, the chance encounters that lead to novel connections. The path is optimized, but the landscape is flattened.

When exploration disappears, so does creative cross-pollination. Ideas become cleaner, faster, and more direct—but also more predictable.

4. The narrowing of intellectual horizons

Perhaps the greatest loss is plurality. Search results presented a spectrum of perspectives, even when they conflicted. Users had to navigate disagreement and form their own synthesis.

Answer engines tend toward consensus. One response replaces many voices. Conflict is resolved upstream, out of sight. While this makes information easier to consume, it also narrows our intellectual field of view. Diversity of thought gives way to probabilistic agreement.

In a world where one answer feels sufficient, curiosity shrinks. We gain speed—but we lose breadth. And over time, thinking itself becomes more uniform, less contested, and less alive.

Are Answer Engines Making Us Smarter or Just Faster?

The strongest defense of answer engines is productivity. And it is a compelling one. For many tasks, answer engines dramatically reduce time-to-decision. A developer stuck on an error no longer needs to comb through Stack Overflow threads. A researcher can summarize unfamiliar domains in minutes instead of days. An operator can ask for a step-by-step process and move forward without hesitation. In these contexts, answer engines don’t just save time—they often lead to better outcomes.

Speed, here, is not trivial. Faster feedback loops mean fewer blockers. Decisions that once stalled teams now happen in real time. For developers, answer engines compress years of accumulated tribal knowledge into instantly accessible guidance. For researchers, they lower the cost of exploration, making it easier to test hypotheses and identify promising directions. For operators, they act as always-on copilots, reducing errors and increasing consistency. In measurable, operational terms, answer engines are undeniably effective.

But productivity is not the same thing as intelligence.

This is where the paradox emerges. Intelligence is not defined solely by the quality of the final answer. It is shaped by how we arrive there—by the questions we ask along the way, the assumptions we challenge, and the uncertainty we tolerate. Traditional search forced users to engage with ambiguity. Multiple links meant multiple perspectives. Conflicting sources demanded judgment. The act of searching required the user to remain mentally present throughout the process.

Answer engines collapse that process into a single, polished output. The uncertainty is resolved before the user ever encounters it. While the answer may be correct—or at least plausible—the cognitive work of grappling with alternatives is quietly removed. Over time, this changes how we relate to information. We stop asking “Is this right?” and start asking “Can I use this?” The difference is subtle, but profound.

Speed amplifies this shift. Instant answers eliminate the productive pause—the moment where doubt, curiosity, or deeper reasoning might emerge. There is no time to wrestle with ideas, to sit with incomplete understanding, or to explore why something works instead of merely how. Reflection becomes optional, and eventually, rare.

So the question is not whether answer engines make us more productive. They clearly do. The real question is whether constant speed is training us to value outcomes over understanding. If intelligence is partly the ability to navigate uncertainty, then tools that remove uncertainty too quickly may leave that ability underdeveloped. In gaining speed, we may be losing something quieter—but far more difficult to recover.

The Educational and Societal Implications

1. Learning in the Age of Answers

Education has always been as much about the process of thinking as it is about arriving at the correct answer. In the age of answer engines, that process is increasingly being bypassed. Students no longer struggle through a problem, test assumptions, or follow a chain of reasoning. Instead, they jump directly to a polished conclusion generated in seconds.

This shift creates a dangerous gap between knowing an answer and understanding a concept. When an answer engine explains a mathematical proof, summarizes a historical event, or writes a piece of code, it often compresses hours of cognitive effort into a few neat paragraphs. While this feels empowering, it quietly removes the mental friction that produces learning. Students can complete assignments, pass quizzes, and even sound articulate without ever internalizing the logic behind what they’re submitting.

Over time, this trains learners to value output over comprehension. The habit of asking “how does this work?” is replaced with “what’s the answer?” Learning becomes transactional rather than exploratory, and education risks turning into a validation loop where the goal is correctness, not curiosity.

2. Expertise Dilution

Answer engines also blur the boundary between expertise and access. When everyone can generate expert-sounding explanations on demand, the social signals that once distinguished deep knowledge from surface familiarity begin to erode. Fluency replaces mastery. Confidence replaces competence.

This creates what can be called the illusion of knowledge. People feel informed because they can articulate answers, but that articulation is often borrowed, not earned. The underlying mental models—the things that allow experts to adapt, critique, and innovate—are missing. In professional and academic settings, this makes it harder to tell who truly understands a subject and who is simply echoing synthesized information.

The danger isn’t that non-experts gain access to knowledge—that’s a genuine positive. The danger is that everyone starts to believe they understand more than they do, reducing humility, discouraging deeper study, and weakening respect for true expertise.

3. The Centralization of “Truth”

Perhaps the most profound societal impact is the quiet centralization of truth. Search engines presented many sources and forced users to navigate disagreement. Answer engines collapse those debates into a single, authoritative-sounding response. Over time, this trains users to accept answers as settled facts rather than contested ideas.

When a small number of systems become the default arbiters of “what is true,” dissent becomes harder—not because it’s impossible, but because it’s less visible. Alternative perspectives, minority views, and emerging ideas are filtered out in favor of consensus and probability.

The risk is not overt manipulation, but intellectual narrowing. Fewer paths to disagreement mean fewer opportunities for critical thinking. And without dissent, progress slows—not because answers are wrong, but because questioning them becomes rare.

This Is Not an Anti-AI Argument

Critiquing answer engines is often mistaken for rejecting AI altogether. That would be a misunderstanding. Answer engines are not a detour from progress; they are an inevitable response to a problem humans can no longer solve alone. The volume of information produced each day has surpassed the limits of individual cognition. No human can read everything, compare every source, or maintain an up-to-date mental model of complex domains. At this scale, synthesis is no longer optional—it is mandatory. Answer engines exist because the modern world demands compression, summarization, and pattern recognition at speeds no human mind can sustain.

The issue, then, is not the existence of AI answers, but how uncritically we consume them. Tools do not arrive neutral; they shape behavior by design. When an interface delivers a single, confident answer by default, it quietly teaches users that questioning is unnecessary. When reasoning is hidden and alternatives are absent, trust becomes automatic rather than earned. Defaults matter because most people rarely override them. Over time, repeated exposure to frictionless answers conditions users to accept conclusions without reflection, not because they are careless, but because the system makes care feel redundant.

This is where the crucial distinction lies: assistance versus replacement. An AI that assists thinking expands human capability. It surfaces patterns, challenges assumptions, and accelerates understanding while keeping the user cognitively involved. In contrast, an AI that replaces thinking collapses the intellectual process into a black box. The user receives conclusions without participating in the reasoning that produced them. The output may be accurate, but the mental muscle remains unused.

The future does not require rejecting answer engines. It requires resisting the temptation to let them think instead of us. The real risk is not artificial intelligence—it is artificial certainty.

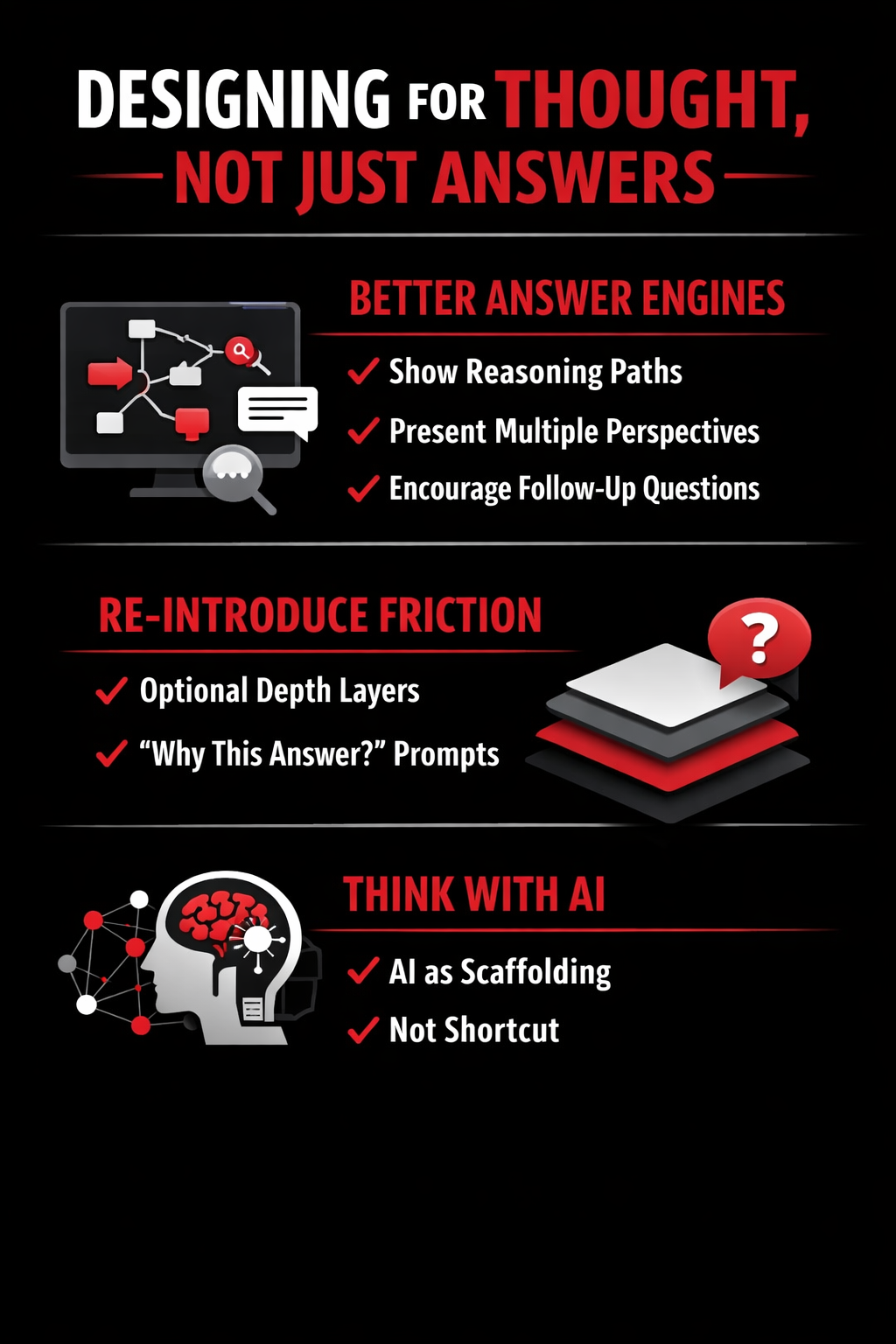

Designing for Thought, Not Just Answers

If answer engines are going to define how humans access knowledge, then their design cannot be neutral. The way an answer is presented quietly shapes how much thinking the user is invited—or discouraged—to do. Today, most answer engines optimize for speed and completeness. Tomorrow’s systems must optimize for understanding.

What would better answer engines look like?

First, they would make reasoning visible. Instead of delivering polished conclusions, they would expose how an answer was formed—what assumptions were made, which factors mattered most, and where uncertainty remains. Seeing a reasoning path does not slow users down; it helps them audit the answer rather than accept it blindly.

Second, better systems would present multiple perspectives by default, especially on complex or subjective questions. Reality is rarely singular, yet answer engines often flatten nuance into one authoritative response. Surfacing alternative viewpoints—mainstream, minority, or conditional—restores the user’s role as a judge, not just a recipient.

Third, they would actively encourage follow-up questions. Instead of closing the loop, the interface would open new ones: What would change if the assumptions were different?, Who might disagree with this?, What’s the counterexample? Curiosity should be designed in, not left to chance.

This leads to a critical concept: re-introducing productive friction. Friction doesn’t have to mean slowness. It can mean optional depth. Answer engines could offer expandable layers—summaries on top, deeper reasoning beneath, raw sources below that. Users choose how far they want to go, but the path is always visible.

Simple prompts like “Why this answer?” or “What were the trade-offs?” can subtly nudge users back into thinking mode. These are small design choices, but they restore agency.

Ultimately, the goal is not to make AI think for us, but to help us think with it. AI should function as scaffolding—supporting cognition while it’s being built—not as a shortcut that replaces it. Scaffolding disappears as understanding grows; shortcuts create dependency.

Answer engines don’t have to train us to think less. But only if we design them to respect thinking as a feature, not an obstacle.

Conclusion: The Choice We’re Making Every Day

The shift from search engines to answer engines hasn’t arrived with a dramatic announcement. There was no clear breaking point, no collective decision. Instead, it crept into our daily routines quietly—one helpful answer at a time. And with that convenience, we’ve accepted a subtle trade: less effort, less engagement, less thinking. We save time, reduce friction, and move faster. But speed has a cost. When answers arrive fully formed, we no longer practice the small acts of reasoning that once accompanied every search: comparing sources, questioning intent, and sitting with uncertainty long enough to form our own conclusions.

Google trained us to search. Over years of repetition, it taught us how to frame questions, refine queries, and navigate imperfect information. Search required participation. It demanded that we think alongside the machine. Answer engines, by contrast, are training us to stop. They collapse exploration into conclusion, replacing a process with a result. What disappears isn’t just clicks or traffic—it’s the mental involvement that once made information meaningful.

This doesn’t mean the future must be framed as a choice between search engines and answer engines. That binary misses the real issue. The question isn’t whether answers are bad or search is obsolete. The real choice is how much thinking we are willing to outsource. We can use answer engines as tools that support reasoning—or as substitutes that quietly erode it. The difference lies in how intentionally we engage with them.

Convenience is one of the most powerful forces in technology adoption. It always wins in the short term. But thinking is what made search valuable in the first place—not the links, not the rankings, but the cognitive effort search demanded from us. As we move toward an answer-driven internet, the most important decision isn’t which tool we use. It’s whether we remain active participants in our own understanding, or become passive recipients of conclusions we no longer question.